I love buoys, but it's not what you're thinking. I'm talking the rotund, fluorescent type. Fishing is my thing and all the trappings of industry that come with it: nets, floats, anchors, crab pots, nylon rope and plastic buoys. It runs in the family. My great grandfather and his brother were fishermen, and owned a boat together. After a dramatic falling out, the stubborn (let's face it, stupid) siblings could come to no agreement, divided everything including the boat and sawed the vessel plain in half. So let's just say the politics of fishing is in my blood.

The beach at Dungeness is pockmarked with the debris of centuries of fishing politics. By the time we hit the shoreline, most of the fishermen are out at sea or in at home, and we give ourselves licence to rummage through these remnants. Between the Turner skies and rose-coloured seas, rivers of shingle nestle a good haul of fishing paraphernalia. Our catch, in pictures, as follows:

We trip over a rope winch pulled taught against the shingle, and Neco, walking beside me, drags up a memory:

"You know, this is how they took Constantinople?'

'With rusty engine winches?

'No, no. They said it could never be taken by sea, but the Ottoman's surprised them.

They dragged their boats over land and attacked from the behind, in sea to the North.'

The Byzantines fell for it. Boats and politics at war again.

Among tarred wooden huts exploding ancient nets, we gravitate towards the snack-shack on the promise of fish flatbreads. Poking a head through his open door, we get talking to the fishmonger next door about a bass. Dressed in wellies and woolly jumper, he tells us that 78% of the quota in the English Channel goes to French boats. The remaining 22% is shared between the Dutch, the Belgians and the English, which means about 10% of the Channel's catch comes to the UK. When the quotas were set, the French set their sights, estimated high and the EU went for it, hook, line and sinker. "We should have done the same" he laments, but his bass is still the freshest I've tasted.

"There were 29 boats here in the eighties. There are only four of us now."

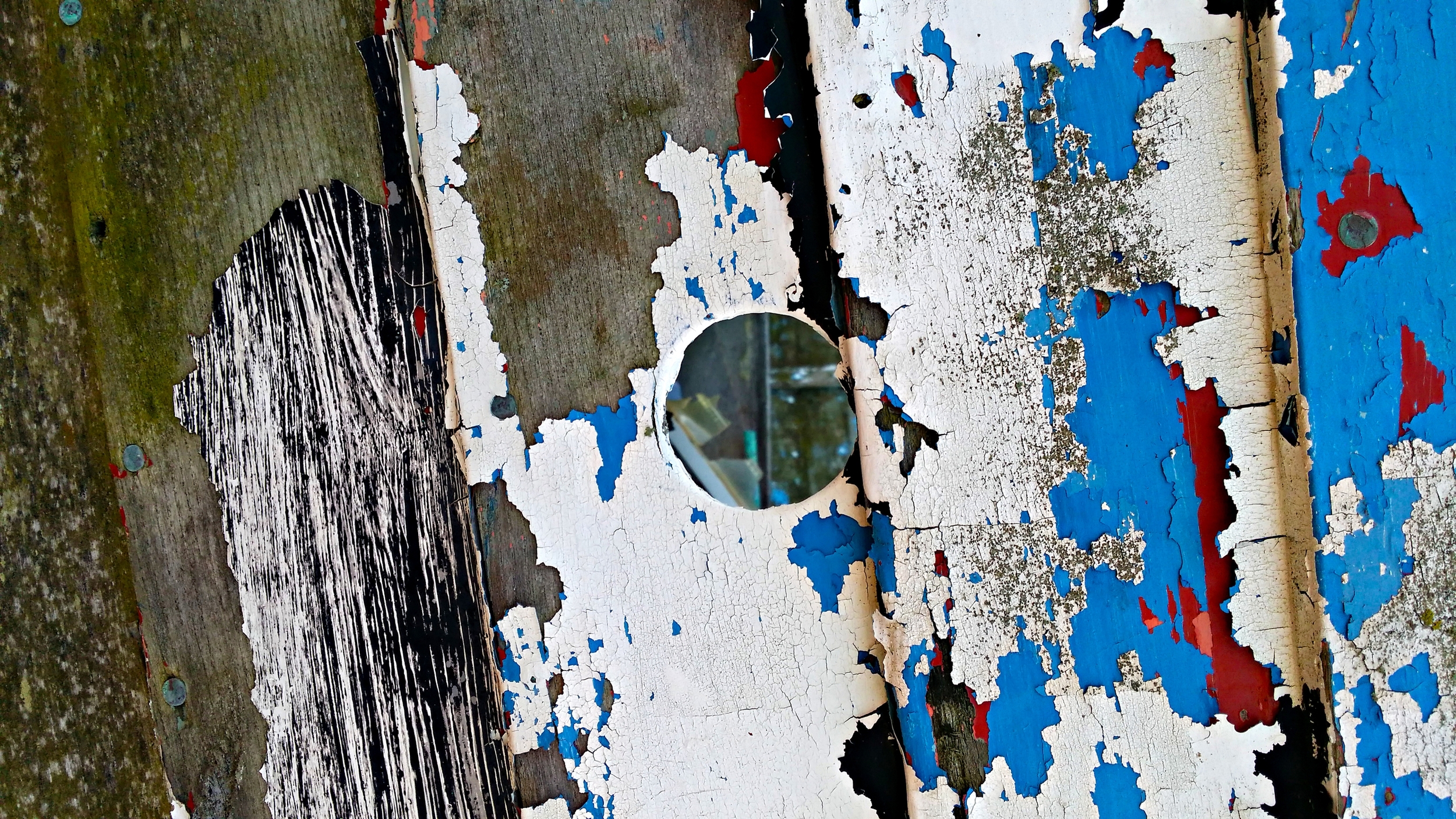

The quotas are clues to the boat skeletons left here, shored up like a working graveyard. They say there were four fishing families in Dungeness who trace their trade back generations: the Tarts, the Oilers, the Thomases and the Richardsons. “My son went out on the boat at midnight last night,” explains our fishmonger, me in shock at the 12am commute, “it was his anniversary, so he had to celebrate before.” Their family use static net fishing on the Annalouison, but it's a tough way to make a living on in-shore fishing boats. “Fish blood everywhere, crab brains all over you!" laughs the artist, Paddy Hamilton, on life on a fishing boat. "It's carnage. And you’ve got to stay out the way of the drunk Russian tanker pilots powering on automatic down the Channel.”

Families hold fast, but practices evolve. Paddy reminisced about his boat-trips out with the fisherman. “They set their GPS to a point on the buoy and off they go. The best thing is when you close in on a buoy, the boat GPS sets its position to stay 3 metres away and just keeps moving,” and he dances back and forth in a fishing boat shuffle to impersonate the shifting hull.

"You can do that," says fishmonger, suggesting there's more to it. “You can follow all the boats on AIS, and call up the others to give you a wider berth.” AIS turns out to be a ship-spotter's digital wet dream: marine traffic websites tracking the movements of any shipping vessel in the world. Right now, the Riike Theresa tanker is headed to Las Palmas, the Stefan Sebum cargo vessel to Casablanca, and the Doreen T to Dungeness, all passing through the coastal waters off Kent, thick with vessels. It occurs to me that we call this 'The English Channel', which must have the French in bits: The English Channel!? A bit rich Britain laying claim to the whole stretch of water? The French call it La Manche, 'the sleeve', and if we can't agree on a name, what hope is there for the fishing rights?

Politics aside, there will always be the anglers, lining up like human markers along the shore. Angling is a waiting game. Slow and solitary, anglers pass the time staring out to the chameleonic sea and channel-flicking as tankers cruise a continuous course past. But the wait comes good: the weekly catches yield plentiful dogfish, dab, codling and pouting, and too many dreaded whiting, aided by 'The Boil'. A side-effect of the power stations' outflow pipes, the boil is a patch of waste hot water pumped into the sea and enriching life on the sea bed: a nuclear jacuzzi.

Dungeness offers no neat and happy ending. It just isn't that kind of place. This seaside desert is full of contradictions: a fishing-rope tug of war between wild sea and shingle; anglers and anti-nuclear activists; fishing boats and politicians. But you get the sense that if any of these fell here, Dungeness would shape-shift its identity, pick up another narrative thread and run with it.