Tripe / Tripas

An unusual place to start thinking about dinner, but we have Lin Yee to thank for that. Her tripe-obsessed project takes a new angle on innards, and Tripeiros, as people from Porto are called. Shopping for cows stomach isn’t everyone’s idea of a great time, but she’s in good company. On childhood vacations my relatives would show off the neighbourhood display of intestines as a matter of pride. It became an initiation rite into local culture, and so this tripe tour of Porto takes on an air of nostalgia. Our third partner in crime is Bruno, a renowned carnivore who knows the ins-and-outs of every butchers' shop in town and whose love of tripe is not for the squeamish.

To eat is to exchange, and as we tour we trade blood tales from China, Naples and Northern Portugal; pork blood cubed and jellied; blood-enriched chocolate sauce and stew. Bruno trumps us with an account of pig slaughter: holding the cord around the pig's neck while his grandfather finished the job. “The blood went everywhere. I looked like a ten year old who’d brutalised a whole village.”

I know what you're thinking. What a holiday? If you're in London, the closest you'll get to such a tour is The Tripe Marketing Board's genius that is Tripe-Adviser. But in Porto – of all places – tripe is taken seriously and every part of the animal is used. On the spotless counter at Carnes Silmor we count lungs, lips, pigs tails, blood cakes. True to Porto's past, tough times demand we're inventive with cheap cuts. Lin Yee takes it to another level and sees appeal in its coral-like texture. She spends hours the next day scanning honeycomb tripe for the travelogue, and in black and white it takes on the feel of folds of a wedding dress. Meanwhile, intestines go down well with our unsuspecting guests: parchment white, cut into two inch lengths, battered until crisp and served with lemon and salt. And so the meal begins.

Greens / Verduras

A matriarch with wraparound shades commands the corner plot at Bulhão Market. “I like to spread the love,” jokes Bruno, as we walk from stall to stall surveying swathes of veg, and buying a little of what we fancy from each. White-haired ladies line the crumbling aisles, and address him as "meu filho" my son, "meu amor". There's nothing like a spot of market shopping to boost your confidence.

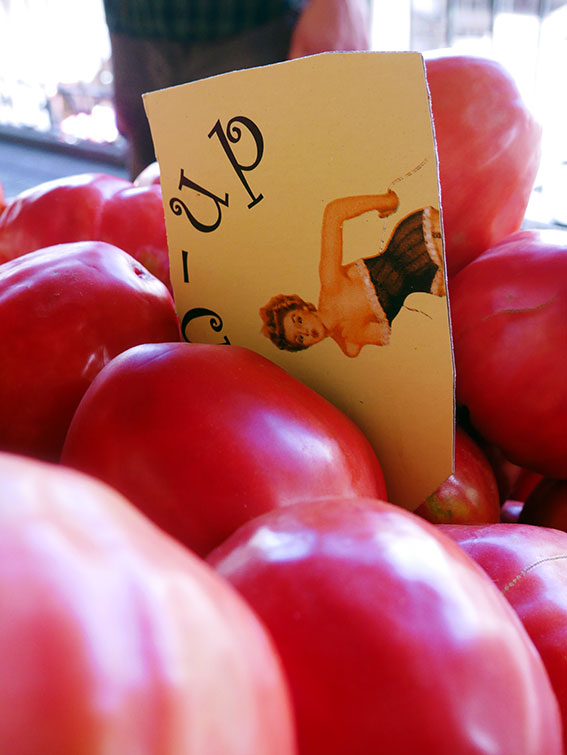

We gather onions and ask our matriarch for a photo that costs us a cool 25 cents. But peddling vegetables doesn't pay the bills, and you can't blame these ladies for trying to make a little extra. A couple of stalls down, our permed stall-holder jerks her finger towards an unplugged chest freezer. We pull out fat-bottomed aubergines to char on the barbecue and smash down with tart garlic and grassy olive oil. We side-step towards weighty beefsteak tomatoes, gnarly and ugly and big as our heads. They smell of deep green in the way only a hot-country tomato can. Sliced up that evening the flesh is marbled with reds and pinks. “You don't want blueberries?” hawks the vendor wife. “Maybe a pack of chillis?” She's got the hard sell which is why she's got the biggest stall. It's a husband and wife operation, and I spot a secret pin-up hiding on the back of a hand-cut price tag that nestles among the tomatoes. I imagine this must be his hidden respite from his pushy mulher.

Back in the kitchen, Ana’s thing is greens and she makes magic with them. Two good handfuls of ruler long beans are tossed and fried tempura style, served with paper-thin lemon slices. Crisp green, sweet and floral. Courgettes are cut into chewing-gum-thin slices, rubbed with salt, sugar, lots of garlic and savoury rosemary. Left to wallow for a couple of hours then rinsed, they transform into a semi-cured ceviche of zucchini. Sweet potatoes soak up a smokiness as they're slow roasted over coals. Cut into melting chunks, they meld into a salad, their softness contrasting with the bite of apple and garlic slivers. “This was so good it made me cry,” say the Kuwaiti girls and Ana beams proud.

None of this is traditional, but no-one seems to have cared too much for vegetables in Portugal. The earth, a terra, was always the last resort for food. Some people say greens represent a hand-to-mouth peasants' past that people are keen to forget. Meat is equal to wealth, but these are not wealthy times and there's less need for a heavy meal to set you up for a day's hard manual labour. Tastes are evolving as influences from outside infiltrate: “I am a purist,” says Ana. “Thats what I like about Nordic cuisine. You know, BAM! Just a turnip,” and cracks a wry smile.

Meat and Offal / Carne e Miudezas

The butchers shops have a particular look: a post-modern 80’s vibe brought about by chilled grey granite and pink fluoro lighting. At Carnes Silmor, we step into immaculate meat lockers, like closets kept for best. Out back, butchers heave heavy half-moon knives as they expertly cleaver each carcass. Hosepipe lengths of paprika smoked linguiça sausage are slung around hooks on the back wall. Layers of secretos line well-kept glass counters: a Portuguese secret as the most tender part of the black Iberian pig.

We stop into another Talho to see what’s good, and pick up a plump veal heart. The manicured butcher carefully wraps the organ, and hands it back in a dove grey bag borrowed from an Italian children’s boutique, printed with the words 'sogno di bambino'. “You have to pay for bags now,” says Bruno as if to explain the bizarre combination of a heart packed into a little boy’s dream.

In the kitchen, we’re shown how to dissect it and it forms the base of a flavoursome stew braised until melting on the barbecue. Sweet with onions, made earthy with livers, then seasoned with bay and just enough chilli to make you blink. Portugal can handle a little spice, a taste that connects to colonial times and a piri-piri punch that's been brought back. A few nights earlier Filó, Porto's beloved Angolan chef, hands me a grin along with an industrial sized jar of piri-piri for which she is known. "In Africa, we make our moamba really spicy," she says, "But I let everyone here choose for themselves."

Bruno gives us a gift of oxtail. A shank lies out on the side which Lin Yee learns to cut under his guidance. It’s braised until almost sticky with tomatoes and deep red wine, while we’re entertained with teenage stories of riding bulls drunk (it only happened once). At the end of the night, Casey lifts the lid off a vat of Arroz de pato: soupy duck rice, laden with duck meat, blood sausage, linguiça and bay. Some guests are on the verge of an Irish goodbye, only to have the waft of meat and rice reel them back in, plates in hand.

Salt Cod / Bacalhau

The tang of salt cod gives a sharp slap up the nose as we turn the supermarket aisle. One-metre slabs of bacalhau lay loose in a corner, mummified like ancient artefacts collected from faraway seas. Organised by different grades from miudo (a little one up to 0.5kg) to graudo (a grown cod up to 3 kg) the oceans of origin are also noted. The dark waters of Iceland or Norway seem at odds with the shrill heat of an August Porto day.

Deema asks a reasonable question, “Why do you go so far for fish when you have so much right here in the Atlantic?” Bruno introduces me to Fernando Pessoa’s ode to Portugal A Mensagem, The Message, and it offers a roundabout answer. Entitled ‘O Mar Portugues’, The Portuguese Sea, the whole of the second chapter represents past glories. The sea is hailed by Pessoa as a memory of the Portuguese talent for exploration: a small nation which turned its back on Europe, set its sights afar and navigated the globe. And bacalhau, a by-product of those ancient mariners, is a taste of that past once nicknamed fiel amigo or loyal friend.

Each season, the famed White Fleet crossed the Atlantic to set sail for the cod-rich waters of Newfoundland. Woven into the folklore of Terra Nova are the dory boat men who each day handlined cod, then split, gutted, and salted for sale months later on the mainland. Now, mothers of Portuguese friends abroad still send packs of salt cod with love, a memory of home and icon of identity for their emigrant offspring.

Days of soaking soften the rock hard flesh as Portugal’s past awakens and takes on a whole new texture. The ritual of desalting a bacalhau takes time, more than we have this evening, so we come up with an alternative. Our salt cod is whipped into an addictive bacalhau a bras: shredded, worked through with stick thin potato chips, softened onions, bound with beaten eggs and flecked fresh parsley. I enjoy it so much I eat it for breakfast the next morning.

We buy a dried miudo slab just to show our guests. Ana pierces it with a good thwack and it's hung on the door:

the first part of an impromptu sculpture of sea, land and people. With a bit of digging, I find the fabled poem which is suitably dramatic:

"Salted sea, how much of your salt comes from tears of Portugal!

Mar Português

O mar salgado, quanto do teu sal

Sao lagrimas de Portugal!

Por te cruzarmos, quantas mães choraram

Quantos filhos em vão rezaram!

Quantas noivas ficaram por casar

Para que fosses nosso, o mar!

Valeu a pena? Tudo vale a pena

Se a alma não e pequena

Quem quer passar além do Bojador

Tem que passar além da dor

Deus ao mar o perigo e o abismo deu,

Mas nele é que espelhou o céu.

A Mensagem

Fernando Pessoa

Octopus / Polvo

Sara the fish wife, seems nervous. The three plump octopuses we had our eye on a minute ago have now swiftly disappeared. “You know what’s happened?” says Bruno “There’s an inspector circling the market.” Sara tries to look busy, frantically scaling a sea bream, as we arrange to rendezvous for the polvo in twenty safe minutes.

Meanwhile, we swap stories to pass the time: of a Galician friend who could read an octopuses mind, stalking rock pools to return with a glut of 20; Of immense pulpada octopus parties, where cooks dressed in white lab coats to protect from smears of black ink; Of one grandfather returning with 6 huge olive oil cans full live squirming creatures, ready for the deep freeze. There's something lavish about an octopus that makes for generous anecdotes.

That evening, our eight legged friend is made into a fresh salad: braised and chopped purple with garlic, onions, parsley and pepper. This classic makes an unlikely madrugada comeback, as we leave a club a couple of nights later and Sergio tells me he’s off to eat an octopus salad sandwich.

Fruit / Fruta

Sol, sol, sol! The sweet Mediterranean climate brings abundant fruit harvests. I always think of Portugal as Atlantic, but Ana reminds me that it dips a southern toe in Mediterranean waters. We pick from its bounty; Seven-year melons encase striking white flesh and black seeds; Green and dusty purple figs, still small as it’s early in the season; Jen and Jess bring a peach they find growing wild at the granite works; Wine-sweet grapes from the Algarve are bought to accompany strong São Jorge cheese; A fragrant pineapple gets forgotten, but we discover two types exist in the Portuguese-speaking world : ananas, and abacaxi, a sweeter variety that Brazilians blitz with hortelá mint.

People / Gente

Ok, they're not on the list but good people are always the main ingredient. Kate's hand-drawn Rooster of Barcelos is slowly surrounded by snippets of conversation. Ideas exchanged from Finland, Kuwait, Italy, Russia, Lebanon, India, Israel America and Berlin make for a heady mix. Behind the symbol that adorns every tourist tablecloth in town is a story of a foreign traveller to Portugal who was saved by a culinary miracle (and, no, that's not Nandos). Bruno has a theory that it was the cook's ingenuity, rather than divine intervention, that caused the roasted cockerel

to crow, and the alternative history seems appropriate tonight.

Dessert / Sobremesa

No one makes it to dessert. Bags of sugar are left unsealed, eggs unbroken, lemons unskinned. Guests normally bring a sweet, so Ronit tells me the story of her mother Malka’s cheesecake. She passed away some years ago and it's traditional in Israel to commemorate the date. Food is so tied up with memory that the family makes a meal. She wasn't renowned as a great cook, and her Friday night offerings were often one colour: everything white or everything red. As part of her white meals she often made a wonderful crumb cheesecake, so good, it’s now made it onto the menu at Ronit’s husband’s restaurant.

Mika ends the meal with an evocative turn of phrase. “These sundown sessions were like dessert,” he says. A sweet surprise at the end of each day, a pause that turned the conversation over.